The True Depth of Your Core and How Yoga Can Help Develop Core Strength

/I hear it all the time “I really need to work on my core strength”. People say this for many reasons: back pain, a few extra pounds, balance, poor posture, a general sense of dissatisfaction. Most of the time when saying this they’re referring to the front side of the abdomen. And let’s face it, it’s the part we can see so it’s the part we pay attention to the most! But what if I told you that your actual core was not just your abs AND, maybe even more importantly, your core was actually something to think about in 2 different depths in your body? Here’s a simple introduction to two possible ways to think about the true depth of your core and how yoga can help develop core strength.

Let me preface everything I say here with the following: your body is an incredibly complex system and no one system can be separated out entirely from the rest in practical application. This is also true for your muscles. We can take individual muscles or groups of muscles into consideration as a model to start to understand our bodies better, but just know that the interrelationships between individuals and groups within the whole is complex and beyond the scope of a single blog post. What I give you below is a model for how to think about and work with this one system within the body that we know as our core.

Deep Core

As I mentioned above, I really think about the core in two different ways. The first way is what I would refer to as the Deep Core. In anatomical language, what is superficial is closer to the surface (in other words, just under your skin) and what is deep is, well, DEEP! So this first way to think about core involves some things that you can’t necessarily touch with your hands.

The first of those is your SPINE. In discussions of Core, this is often overlooked, but if we consider the core to be at the center of our body, we have to first consider the bony structure that is not only at center, but is an attachment point for many muscles that we might think of as Deep Core muscles. It’s also worth noting that most of us, because you can feel your spine through the back side of the body (just put your hand on the back of the base of your neck. That bony bump that sticks out is actually your C7 vertebra), don’t have a good understanding of just how deep the spine goes into the abdomen. I can’t give you definite measurements, but trust me, it’s pretty deep!

Now we get to the muscles of core and here is where, in my mind, I start to make some distinctions. Generally speaking, the muscles that run along and attach to the spine are muscles that mostly create spinal (or deep core) stability. Key among these is the psoas. This large muscle is often thought of as a hip flexor, but in reality, it’s PRIMARY function is to create stability and absorb shock in the spine. While it does serve a small part in hip flexion (remember, complex system) we can see that the bulk of the muscle is much more focused on the spine, simply by looking at how many more muscle fibers are near or attaching to the spine versus the hip joint.

There are many other deep muscles that stabilize the spine include the amazing network of interspinal muscles and the erectors. Rather than getting bogged down with names and details, simply understand that there is the deep level to core that is centered near and surrounds the spine.

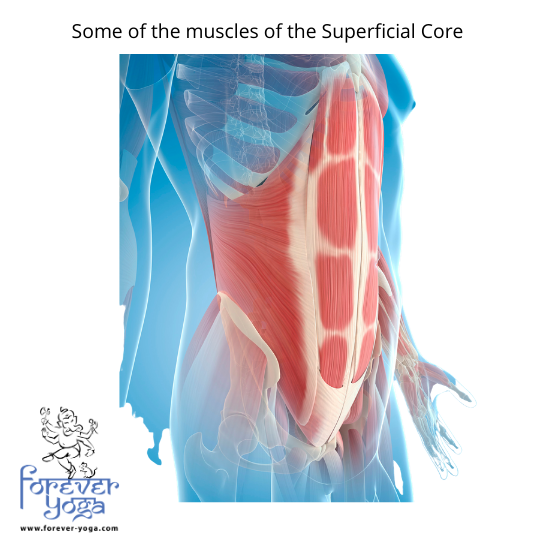

Superficial Core

There is this second level of core as I think of it. This is the one that most of us think of that includes the abs. However, a key concept here is, just as in the deep core, it’s not just the front! Generally speaking, the Superficial core is a full circumference network of muscles around the abdomen that mostly create movement. This includes your abs on the front but also includes your obliques (the sides of the cylinder), your lats (the back) and other layers of muscle. These muscles are fairly large and while they do contribute to stability, they can mostly be thought of as being responsible for movement such as flexing your spine, extending your spine, twisting and side bending. Therefore, to focus on only one set of these muscles is to loose sight of the full picture of what constitutes core.

So we have a Deep Core network of muscles that is close to the spine and generally creates stability, we have a Superficial Core network of muscles that is closer to the surface and generally creates movement. This basically describes a cylinder that has a center within it. Something like this:

So what about the top and bottom?

In my mind, the top and bottom are shared between these two levels (Deep and Superficial) because they cover both. The bottom is the network of muscles that make up the pelvic floor. The top is your breathing diaphragm. If you’ve never seen it before, it looks something like this:

The umbrella like shape of this muscle puts a lid on our cylinder, connects to the spine but also connects in close proximity to those Superficial Core muscles around the outside. The pelvic floor works similarly. These structures create stability but are also key in movement throughout this complex system.

What It All Means

With this understanding that there are two main layers to our core as well as a top and bottom, we now see that the things we might always think of when it comes to core work, namely sit ups, really are addressing only one thing - the superficial muscles on the front side of the abdomen. Now also try to imagine that this was the ONLY thing you focused on when trying to strengthen your core. It becomes obvious right away that this would create an unhealthy and unhelpful imbalance. We need to work all these structures to bring a balance of strength and flexibility to the entire system in order to be well, similar to any other point of focus in the body.

How Yoga Can Help

While a vinyasa yoga practice can’t necessarily address the full picture of core strength, there’s a lot that we CAN do to holistically address the deep and superficial core in our sequencing as teachers and in our practice as students. Here are some ideas:

Rooting down through the feet in standing postures - this kind of engagement, especially before transitioning from close to the earth into a standing posture (think moving from low lunge to Warrior 2) can activate those stabilizing muscles of the deep core including the psoas. There is a complex network of muscular connections between the psoas and your feet (see the work of Tom Myers if you’re interested in learning more). When you engage in this way you’re helping to support the spine through transitional movements and creating that deep core stability those deep core structures are there to do. (For more about the benefits of rooting down in standing postures, see this blog post.)

Lifting high enough in Ardha Uttanasana (half way lift) - it’s a posture most people hardly give a second thought to in their practice, but actually lifting up in this posture can help to work the back body muscles and create more strength. Even better, think about that support coming from the front and the back. More on that here.

Create twisting actions without leverage - many yoga practitioners use their arms to help create leverage for deeper twists. This isn’t wrong. However, if you want to build core strength, especially in the muscles of the core that create rotation, consider doing your twist WITHOUT the arms involved. You won’t go as deep, but you’ll certainly create more strength in these important side body muscles.

Incorporate more locust poses into your vinyasa - resisting gravity is a key way to build strength in a yoga practice and there’s almost no better pose to embody that than locust. When working with this posture, be sure to do your best to not just bend the knees when you lift the legs. See that the lift is actually coming from the use of your back body muscles like glutes (they’re part of your core!) and hamstrings.

Use the breath in coordination with movement - This is especially useful in movements that create a lot of force or load in the body. One of my personal favorites as a person with back injuries is to EXHALE on the way up to standing from a standing forward fold.